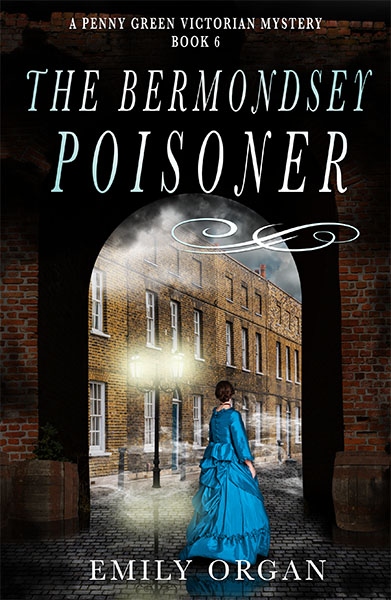

A trail of suspicious deaths and a culprit who can’t be caught.

Journalist Penny Green is reporting on what seems to be a straightforward poisoning case in Bermondsey. But then a series of macabre photographs comes to light. Memento mori with a twist.

When Scotland Yard begins exhumations, Penny and Inspector James Blakely are daunted by the size of the investigation. The case is brought to a simple conclusion when the poisoner confesses. Or so everyone thinks.

As the body count rises, the search extends across London to the warren of caves beneath Chislehurst. Few can match the cunning of a serial poisoner. Not only is Penny outwitted, she could also lose her livelihood.

The Bermondsey Poisoner is book 6 in the Penny Green Victorian Mystery Series. Available as ebook, paperback, hardback and audiobook. Free to read with Kindle Unlimited.

Book 1 – Limelight

Book 2 – The Rookery

Book 3 – The Maid’s Secret

Book 4 – The Inventor

Book 5 – Curse of the Poppy

Book 6 – The Bermondsey Poisoner

Book 7 – An Unwelcome Guest

Book 8 – Death at the Workhouse

Book 9 – The Gang of St Bride’s

Book 10 – Murder in Ratcliffe

Book 11 – The Egyptian Mystery

Book 12 – The Camden Spiritualist

Read an excerpt from The Bermondsey Poisoner I walked down to the river the following morning, passing the stone walls and turrets of the Tower of London. It was a warm, late-summer day but the sky was grey. I removed my jacket and unfastened the top button of my high-collared blouse in an attempt to cool myself down. Beyond the river, the chimneys of south London darkened the air with clouds of smoke. I had heard that a new bridge had been proposed that would cross the Thames from the Tower of London to Bermondsey, but for the time being the quickest route was via the Tower Subway. I paid my halfpenny toll and climbed down a long spiral staircase to the tunnel, which ran beneath the river. The Tower Subway was not designed to delight the senses; it was a tube lined with cast iron and lit by a row of dim lights. Water dripped down the walls and the wooden walkway was unsteady in places. The slightest noise echoed along the tube so that a conversation being held fifty yards away sounded as though it were level with one’s shoulder. I strode as quickly as I could and thought about Francis, who would be departing from Liverpool at that very moment. I had already encountered his replacement in the reading room at the British Library. His name was Mr Retchford, and he was a dough-faced man with small, pig-like eyes and a shrill voice. I couldn’t imagine him being anywhere near as helpful as Francis had been. The warm scent of exotic spices from the warehouses lingered in the air as I emerged from the dingy subway staircase on the south side of the river. I walked beneath the railway lines from London Bridge station and found that a new smell assaulted me as I reached Crucifix Lane. Beneath the railway arches were heaped piles of animal dung collected for soaking and softening leather in the tanneries. My stomach turned as a hard-faced woman, seemingly impervious to the stink, emptied a small crate of dog excrement onto the foul-smelling mound. Flies buzzed in my ears and my throat gagged. I covered my nose with my handkerchief and strode along as quickly as possible. Bermondsey was a lively, busy place, where rows of cramped little houses sat cheek by jowl with factories pumping out fumes of chocolate, glue and sulphur. Every spare corner was given over to industry of one sort or another. Machines rumbled and hammers pounded. As I neared Bermondsey Square the acrid odour from the large tanneries caught in the back of my throat. The inquest into John Curran’s death was held in an upstairs room at The Five Bells public house. The coroner, Mr Robert Osborne, was a wispy-haired man with a thick moustache, and he sat at a table with a small group of gentlemen. The jury of twelve men sat on chairs along one side of the room, while the press reporters and members of the public were crammed into what remained of the floor space. I did my best to write everything down in my notebook, squashed as I was between two other reporters. The coroner stated that John Curran had been a labourer at a local tannery and was thirty-one years old when he died at his home, 96 Grange Walk, on the seventeenth of August. Proceedings were halted for a short while at this point as the jury paid a visit to the mortuary in the nearby church to view the body. Once the jury had returned, Mr Osborne called on the first witness, Dr Jacob Hill, who stated that Mr Curran had been unwell for about a week before his death. Mr Curran’s wife, Catherine, had on two occasions summoned the doctor to the home they had shared while he was unwell. “Can you describe the symptoms Mr Curran presented with, Dr Hill?” asked the coroner. “He complained of pain in his bowels and diarrhoea.” “And what treatment did you recommend?” “I ordered for him to take soda water and milk.” Dr Hill reported that there had been no improvement in Mr Curran’s condition by the time of his second visit and stated that he had found Catherine to be an extremely concerned and attentive nurse. He had last seen her when she visited him at his surgery to request a certificate of death. A man representing Prudential Life Insurance Limited deposed that Mr Curran had been insured with the company for the sum of fifty pounds, and a representative from the General Assurance Society confirmed that Catherine Curran had effected a policy on her husband’s life for the sum of thirty pounds. Both policies had been taken out with Mr Curran’s full consent. Mr Osborne then called for William Curran, the brother of John. A young, clean-shaven man with a heavy brow and scruffy fair hair walked up to the table. He held a cap in his hand and wore a smart but ill-fitting suit, which I guessed he had borrowed for the occasion. William Curran stated that he lived in Paulin Street and worked at the same tannery where his brother had been employed. “Were you concerned about your brother before he died?” asked the coroner. “Yes, sir, I was, ’cause ’e’d taken to ’is sickbed.” “And what was his sickness?” “What the doctor ’ere said. Diarrhoea. An’ vomitin’ an’ pains such as ’e’d never ’ad afore.” “And prior to this spell of sickness, would you say that your brother had been in good health?” “Yes, sir. Never ’ad a day of sickness ’is entire life.” “He was ordinarily a fit and healthy man?” “Yes, sir.” “And did you have any idea as to the cause of his sickness?” “Not ter start wiv. I thought ’e’d get better, but it was when she stopped me seein’ ’im, that’s when I begun ter get suspicious.” “Can you explain who you mean by she?” “Yeah, ’is wife, Caffrine.” “Mrs Catherine Curran prevented you from visiting your sick brother?” “Yeah. I’ve seen ’im once, and when I’ve went back to see if ’e was gettin’ better she ain’t never let me back in.” “Mrs Curran would not readmit you to their home?” “Nope.” “Did she give you a reason for refusing to do so?” “She tells me as ’e’s tired and don’t want no visitors. Well, that don’t sound like our John! I ain’t never known ’im refuse ter see me.” “Did you attempt to visit your brother again after that?” “Yeah, twice more I tried ter see ’im.” “And you were unsuccessful?” “She weren’t lettin’ me in the door.” “In your statement to the police you say that you visited your brother on the twelfth of August, and that was the last time you saw him. Is that correct?” “Yes, sir.” “And why did you inform the police about your brother’s death?” “’Cause she wouldn’t let me see ’im, like I said! I told ’em she’s done summink to ’im. I dunno what, but she’s done summink. It weren’t right.” “What made you think Mrs Curran had done something, as you put it, to your brother?” “‘It just weren’t normal. I smelt a rat.” Detective Inspector Charles Martin of M Division was the next witness. He was a young, fair-haired man with a round, pleasant face and fair whiskers. “I was informed that Mr William Curran had concerns that his sister-in-law might have had a hand in his brother’s death,” he told Mr Osborne. “And what caused you to give credence to his accusation?” asked the coroner. “I wasn’t sure whether to believe it or not initially, sir. It’s not uncommon for the police to receive false accusations pertaining to all sorts of crimes, including murder. However, it is my duty to establish whether there is any basis for the accusation.” “And did you find any such basis?” “My suspicions were aroused, sir, when I went to the address, number 96 Grange Walk, and found no sign of Mrs Curran there. The enquiries I made with her neighbours suggested that she had taken off.” “Have you since established the woman’s whereabouts?” “No, sir. M Division is currently carrying out an extensive search for the woman.” “Can you speculate on the reason for Mrs Curran’s disappearance?” “One possible explanation is that she is guilty of her husband’s murder, as Mr William Curran has suggested. The sudden death of a usually healthy man, the disappearance of his wife, and the existence of not just one but two life insurance policies, led us to decide that a post-mortem examination of Mr Curran’s body was necessary. And the findings of the autopsy suggest that—” “Thank you, Inspector Martin. I shall stop you there as we will hear about the autopsy from the police surgeon next.” Dr Montague Grant had a long ginger beard and wore half-moon spectacles. He confirmed that he had carried out the post-mortem examination and explained that the stomach and bowels had shown signs of inflammation and ulceration, which suggested Mr Curran had consumed an irritant. “And you suspected this irritant to be a poison?” asked the coroner. “Yes indeed, sir, so I removed sections of the viscera and sealed them into three jars, which were then passed to Mr Irving at the Royal Institution.” The analytical chemist from the Royal Institution, Mr Joseph Irving, spoke next. “I examined the contents of each jar according to Reinsch’s test and obtained evidence of arsenic being present,” he said. “I also conducted an examination according to Marsh’s test, which provided the same result. An extraction of the poison from the viscera was then conducted by the Fresenius-von Babo method, which yielded a quantity of arsenic equivalent to one-and-a-third grains from the stomach and intestines. A further quantity of arsenic, equal to one grain, was obtained from the liver, kidneys and spleen. I should add that the intestines had a golden-yellow appearance, which suggests that arsenic was present throughout, and that this was not a case of a single incident of poisoning.” “You believe that more than one dose was administered to the deceased?” “I do, yes.” “And that the amount of arsenic present was enough to kill a man?” “Yes.” Once all the witnesses had spoken, Mr Osborne addressed the jury: “My judgement on the matter is that we must adjourn for two weeks in order to allow the police time to search the home of the deceased for further evidence of arsenic poisoning, and to locate the whereabouts of Mrs Catherine Curran. I propose that this inquest be resumed on Wednesday the third of September.”